The myth of the “deal made with the devil” at the crossroads is an old one, particularly in African and African-American folklore.

And whether or not blues legend Robert Johnson actually made such a bargain with a Luciferian character at a rural Mississippi crossroads in the early 1930s remains a mystery. We do know that such stories only added to the allure of the artist, like Tommy Johnson, a bluesman who made such a sinister “crossroads” claim in order to add to his allure and fame.

It’s a well-known tale in blues, rock and pop music circles. The performing arts are rife with yarns about people becoming overnight successes in their field – be it music or theater or writing – and suggesting that their success could have only been accomplished with the assistance of otherworldly entities who are ready to make a deal.

The price? One soul.

Such is the case of Robert Johnson, a poor, Black man born into a sharecropping family in racist, Jim Crow Mississippi. Johnson never got far in school and had no formal musical training to of which to speak. Yet, he was talented enough to craft some of the most soulful, spellbinding and unforgettable blues ever recorded.

How did Johnson surprise some of the leading bluesmen of his day, from Son House to Willie Brown and Charley Patton?

Those wanting to discount the fact that Johnson was a naturally gifted singer and songwriter took the superstitious route and suggested he struck a deal with the devil at a crossroads somewhere around Clarksdale, Mississippi. After all, in his “Cross Road Blues” (aka “Crossroads”), Johnson outright sings of walking “side-by-side” with the “Devil.”

At the height of his success, after two Texas recording sessions and regional fame, Johnson is struck down at age 27. Poisoned by a jealous man at a juke joint who thought Johnson was trying to take his wife, Johnson’s luck had run out in a wicked twist of fate.

It’s a story with lots of passion, mystery, betrayal and redemption. A classic tale about a man’s rise and fall, briefly escaping life down on the cotton plantation and finding some success, but never quite satisfied and always rambling. The discovery of Robert Johnson would play a major role in what would later be known as rock n’ roll.

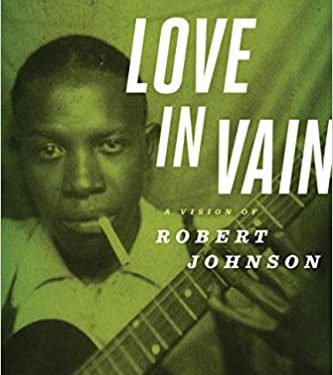

Author and screenwriter Alan Greenberg understood the sheer archetypal drama of Johnson’s remarkable story, and in 1983 crafted a screenplay titled Love In Vain, after one of Johnson’s song titles.

Greenberg’s story – later appearing in novel form – fully embraces the crossroads myth.

The reader is likely to shudder, as I did, when Johnson first encounters the spidery “devilman” at a performance and later in a movie theater. Johnson is intrigued enough by the devilman’s offer, which includes his willingness to “tune” an enchanted guitar his friend Ike Zimmerman gave to him.

Johnson would go through with this arrangement with the devilman, going to the crossroads at midnight. The devilman arrives and tunes the guitar to where it “sounds and resounds like an electric guitar.” Johnson then tips the devilman a dime and, before he leaves, he tells Johnson to “Talk some s**t, man. Talk some s**t,” meaning for him to play. This is the defining passage of Greenberg’s story and the mythical story of Robert Johnson.

“Robert falls down on his knees at the crossroads, strumming a fierce guitar riff as the devilman’s words fade.”

As he sees and hears Johnson playing the guitar as never before, the devilman says, “Won’t nothin’ be the same no more – won’t nothin’ be the same.”

And they wouldn’t be. It would take a few decades after Johnson’s death and his unceremonious burial in an unmarked grave, but 20th century popular music, specifically blues and rock n’ roll, would be dramatically influenced by Johnson’s music and immense talent.

But as the Robert Johnson crossroads myth has been repeated far and wide, it is hard to separate truth from fiction. Greenberg offers a phenomenal account of that time period and Robert Johnson’s role in it, as short as it was.

Johnson’s self-assuredness and cocky attitude, particularly in the face of eternal damnation, is noted when he is conversing with a friend.

“Your soul, it reaps less from knowin’ a little gain tha losin’ a whole lot more, I reckon.”

“Then boy, you goin’ to Hell,” his friend Granville replies.

“Hell ain’t where you dead, man. It’s where you alive,” replies Johnson.

Throughout the book, one can sense that Johnson somehow senses that time is short. Greenberg notes in the first pages of the book, that the “hellhounds” were on Johnson’s trail. And that when his death comes during a “jook” near Three Forks, Mississippi, in August 1938, where his drink is poisoned, it seems as though the “hellhounds” have possessed the famed blues performer.

As the poison courses through Johnson’s veins, the “hellhounds” seem to almost be inside of him, tearing him apart in this equally important passage where he runs out of the building “yelping like a rabid animal, kicking up clouds of dust.”

The “devilman” who snared Robert Johnson is nearby, watching Johnson in his death throes as “Robert scampers like a dog on all fours into the field … (h)e stands and collapses alone.”

But before he dies, and the devilman thinks he has captured Johnson’s soul, Johnson writes “Jesus Christ my saver an redeemer” on a piece of paper before ending up in an unmarked grave in the Mississippi Delta on a hot August day.

Want to reach a local audience and grow your business?

Our website is the perfect platform to connect with engaged readers in your local area.

Whether you're looking for banner ads, sponsored content, or custom promotions, we can tailor a package to meet your needs.

Contact us today to learn more about advertising opportunities!

CONTACT US NOW