PHILADELPHIA — Ten years ago now, and on a Sunday morning in Royersford, Pa., it was time for the gospel reading inside the Church of Charlie Hustle.

In March 2014, Pete Rose had come to Christ’s Church of the Valley, at the cost of a speaking fee that CCV’s leadership council kindly declined to reveal, for a Q&A about “second chances,” and over the hourlong exchange with the church’s pastor, Rose gave the people what they paid for. He said that when he bet on baseball while managing the Cincinnati Reds, when he committed the transgression that earned him banishment from the game and that he lied about for years, he only bet on his team to win. In his mind, his actions were understandable, even justifiable: “Every manager should do that. You should do everything in your power to try to win the game.”

He described Marge Schott, the Reds’ longtime owner, as “the only one in the organization who had facial hair.” He wasn’t “saying Blacks are faster than whites,” he was saying at one juncture of the talk, “but all the sprinters are Black. There’s something about that muscle right here.”

The pews were full. The congregants cheered and laughed and gave him a standing ovation.

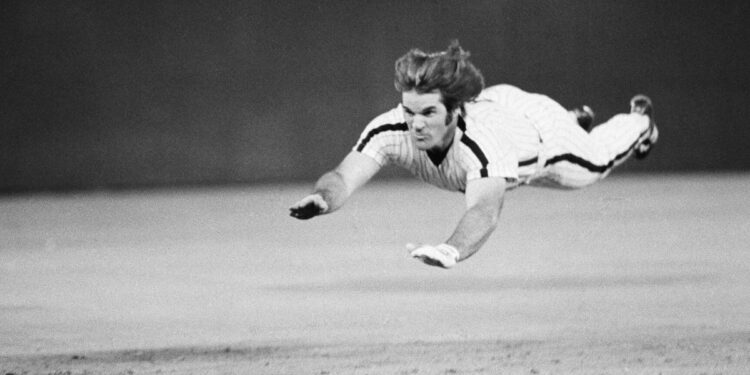

Rose died Monday at 83, and for all the praise one can heap on him for his playing career — the major league-record 4,256 hits, the 17 All-Star Games, the three world championships, his indispensable role in helping the Phillies win their first World Series — there’s almost as much cause to wince and wonder how a person so deeply flawed, so completely self-absorbed, could be a hero to so many.

Here was a man who was a model on the field in every conceivable regard and a cautionary tale off it. Who was the beating heart of the Big Red Machine, those juggernaut Reds teams of the early-to-mid-1970s. Who spent months in prison for tax evasion. Who taught Mike Schmidt what it took to be the player Schmidt always should have been, to be the best third baseman in the game. Who was so blind to everything but his own legacy that for too long he couldn’t bring himself to do the one thing that might have salvaged that legacy: tell the truth. Who was accused of statutory rape, of having sex in the 1970s with a girl who hadn’t turned 16 yet, and who dismissed questions about it by telling a female reporter, “That was 55 years ago, babe.” A man you’d want on your baseball team but nowhere near your neighborhood.

Rose was the consummate example of a famous athlete who insulated himself from criticism by cozying up to media members — or, to put it better, allowing media members to cozy up to him. Step into a clubhouse, sit down for a news conference, and Rose could be charming and revealing and tell an unforgettable story. In the days when newspapers and nightly newscasts were sports fans’ primary vessels for insights and information, Rose’s personality was a currency of infinite value. He was a fountain that scribes would not dare turn off, and if, to drink, they had to ignore and excuse his defects or defend him as if he were a family member, many were more than willing.

Rose helped foster the misconception that being a good quote was the same thing as being a good guy, that playing the right way was the same thing as living the right way, that sports character was necessarily the same thing as real character, and the public was happy to celebrate the only image of him it wanted to see.

He died Monday without having been reinstated by Major League Baseball and without the honor that he longed for most: induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. That MLB and other major sports leagues now accept and profit from gambling often is offered as a reason to reinstate him, to wipe away his sins and officially acknowledge his achievements. And it’s true: There are loads of hypocrisy in MLB’s position on gambling and its position on Rose. But the fact that these leagues have embraced gambling, just for the sake of their bottom line, doesn’t change the unethical nature of an athlete or coach or manager betting on their team. It only makes the leagues themselves more complicit when someone violates that sacrosanct principle, as Rose did.

At Christ’s Church of the Valley a decade ago, Rose started the Q&A with a joke: “I wanted to ask God who’s going to win the game tomorrow, the Cardinals or the Reds?” That was him to the end: entitled, defiant, oblivious to everything but his own aims. What made him great made him ugly. Pete Rose was an immortal baseball player and an amoral human being. Come to terms with that dichotomy however you choose. His death doesn’t make it any less true.

©2024 The Philadelphia Inquirer. Visit inquirer.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Want to reach a local audience and grow your business?

Our website is the perfect platform to connect with engaged readers in your local area.

Whether you're looking for banner ads, sponsored content, or custom promotions, we can tailor a package to meet your needs.

Contact us today to learn more about advertising opportunities!

CONTACT US NOW